Behind the bars with Jail Time Records

Enter the Central Prison of Douala and meet the collective that’s lighting up the mic for current and former prisoners to reimagine the stigma around incarceration, provide a path for reinsertion, and drop heavy tracks from behind bars.

The mic is on. Headphones bump a beat into Empereur’s head. “Laaaapopete” (he’s back) he raps, sweat dripping down his face. There’s no AC here. No luxuries. And nowhere to get any. Not really. “Obina omalaba” (you know you’re hot) he continues in his raspy tone. Around here, Empereur is a leader, a chief. But it’s rugged and dangerous types that follow. A gang. “Laaaapopete, laaaapopete”. Empereur sticks his head out from the booth, more sweat. In the bare bones studio box is a dreaded and confident figure sitting behind a computer, looking back at Empereur, smiling. Around him a ragtag collection of young’ins with tattered clothes sing back, “ndongo” (pepper). Laaaapopete. Ndongo! Laaaapopete. Ndongo! Painted on the wall is a series of shirtless figures, names scrawled beneath in black ink. Israel… Dione… The session is packed. Joyful. Outside of the studio is a dirt alley. Throughout the alley are a series of sheet metal cells packed with beds and contraband. Around those cells is a 2 meter high wall. Atop the wall, the ensnared grip of barbed wire and a sign reading “Prison Centrale de Douala”. Around this sign is New Bell, a working class, immigrant neighborhood of Cameroon’s economic capital. Back in the middle, the chanting continues, the mic is still on, recording. This is Jail Time Records.

Jail Time is a collective founded by former detainee and Cameroonian music producer Steve Happi and Italian artist and NGO volunteer Dione Roach. In 2018, Jail Time built the first music studio inside a prison in Africa. New Bell prison is the country’s most notorious incarceration facility and, in Cameroon, like in much of the world, the stigma attached to convicts and former detainees is a heavy cross to bear. What began as a music project has evolved into a human one, with stories of hope, aspiration, and redemption. Since its founding in 2018, Jail Time has also added a studio outside the prison, in Douala, serving as a reinsertion pipeline where ex-detainees have a place to continue their work, lean on the founders for help, and have a sense of stability in what is often a turbulent and troubling life on the street.

At its modest scale, Jail Time has done much to transform the surrounding public’s perception of who an incarcerated person is and can be. They can be sensitive or funny. Troubled or at peace. They can be role models and artists. They can err without being errors. Guilty or innocent. With a compilation out and the budding Jail Time Productions (providing the visual backdrop to the world inside the prison and life on the streets of Douala) on the way, Jail Time is building a foundation for social change through the power of music. But it isn’t easy. Working with detainees inside requires a saintly patience, and working with former detainees outside requires an ultimate generosity of spirit. Oftentimes lives hang in the balance. Whether it’s the dangers of drug abuse, the violent realities of the street, or the inevitable contact with the force of law that may once again strip away someone’s freedom, Jail Time and its founders have given themselves, and their lives, to the project.

The outside looking in

There’s a seductive allure that emerges from the imagination of prison. Ideas of gangs, unwritten codes, and the terrifying presence of evil. We fetishise it on television, stigmatize it in our social spheres, and glorify it in music. With all this noise it’s hard to accurately imagine the day-to-day reality of an inmate. Both the mundane and the horrifying. It’s easy to dehumanize instead. We slap on labels like “convict” or “criminal”, forgetting the all too human series of follies and misfortune that lead someone to end up behind bars. Even more difficult, to imagine the complicated emotional struggles a person in that environment must confront within themselves.

Like a prisoner, a prison also has a story. Often troubled. New Bell is no different. Historically the neighborhood of New Bell was known as the “Strangers Quarter”. In 1914, during the German colonial regime, the Strangers Quarter of New Bell was created as part of an urbanization plan intending to relocate the local Duala population and the growing number of African immigrants to the outskirts of the city, reserving the center for Europeans and colonial officials. This included a one kilometer-wide Free Zone to separate the populations. A policy which the French kept in place after ousting the Germans in 1916.

As reliance on cheap African labor increased into the 1920s, New Bell, previously left to its own devices, was suddenly instituted with strict controls over movement and settlement, forcibly compelling residents to work for European interests. Those who did not comply were classified as delinquents, the definition and punishments of crime thus broadened and an increasing number of New Bell residents fell under the criminal category (Schler, 2003). Nonetheless, controlling the growing New Bell population remained difficult. Clandestine trade, movement, and resistance to the colonial regime persisted. In 1923, Governor Marchand devised an identity card system measuring the forefinger in order to control and categorize the population. To enforce this growing criminalisation of what residents and colonial agents referred to as ‘The Bush’, a prison was built and expanded to hold a growing number of “non-compliants”.

During the colonial regime the prison was known for its brutality, use of violence, and broad application of death sentences. Into the 1950s, as New Bell became a hub of nationalist resistance and anti-colonial thought, colonial enforces once again cracked down on the native population, overpopulating the prisons, and making no effort to improve standards of living or care. After independence from the French colonial regime in 1960, the prison remained in effect. Decades of conflict, resistance, and mismanagement have left New Bell an underserved community, and its prison a brutal environment for both serious offenders, those awaiting judgment, and marginalized citizens subject to charges of petty crime.

Today, the prison doesn’t appear as anything particularly special. The bustling city of Douala with a population of over 5 million residents sprawling along the Wouri river moves in a hectic buzz around the tall, tan walls, and a modest sign betrays nothing of the history and cruel reality of the prison and those who live inside. Yet, the history of New Bell and its building surrounded in barbed wire have the ancient echo of unfolding time. The diverse population of the prison is a reflection of the port city’s colonial history, the cruel legacy of crime, and the conditions of inmates as the clumsy leftovers of mismanagement and an uncaring administrative arm. Looking back perhaps it all feels inevitable. Permanent. The empty shadow of a cell where history and biography collide.

Prison is a wild world

Steve Happi was born in Douala. From a young age Steve became interested in music, though not necessarily the music of his peers. “I was a weirdo. A teenager from Cameroon listening to electro music,” Steve explains. As early as 16 Steve began producing tracks inspired by European house and other electronic genres. He connected with Avicii on a music blog before the Swedish EDM producer became a global sensation, and looked up to producers like Daft Punk or Swedish House Mafia. From the influence of his older brothers he also picked up on 2000s American hip-hop from Lil Wayne to Rough Riders. Learning to DJ, he would travel for gigs to Morocco, the Mediterranean, and elsewhere, before returning home to begin a Bachelors in International Business Management. Though Steve quickly learned this wasn’t his path, spending more late nights in studios than early mornings in class, eventually deciding to pursue music full-time, with his brothers, launching a local festival, Ça vient de la rue, and a record label, God Made.

Things took a turn when Steve’s father passed away in 2017. Steve, a Christian, had a dispute with his family over the burial rights of his father, who were animists. Unwilling to let his family members decapitate his father in a traditional burial, Steve buried his father on his own terms, without their consent. Members of Steve’s family who worked within the justice system accused Steve and his two older brothers of murder. “It was totally absurd,” Steve recounts, “he died of a heart attack, it was recognised by the hospital. But my father’s little sister, who is a judge, used her position to apply pressure on us.“ Steve and his brothers were taken to New Bell Prison, awaiting trial. He would remain there for two years before the charges were eventually dropped and Steve and his brothers were exonerated of all crimes.

Steve and his brothers were taken to New Bell Prison, awaiting trial. They would remain there for two years before the charges were eventually dropped and Steve and his brothers were exonerated of all crimes.

Steve’s story is unfortunately all too common. Harsh punishments, corruption, and fallout of a penal system that puts pressure on those with no recourse is the norm. Drug possession, vagabonding, and lack of ID, are the types of minor infractions that can snowball into a long term prison sentence, or charges that force people to await trial from the inside, often with little idea on when their court date might be. Some estimates of the number of inmates on pretrial detention are as high as 69%. This, coupled with the lack of oversight and shoddy living conditions, can lead to a physical and psychological rot that transforms an already vulnerable population into hardened criminals.

“Prison is a wild world man…” Steve says, remembering the night he entered New Bell. “You arrive at night and straight away you see thousands of people behind bars. These strong faces in the night, criminals, screaming at you, ‘Fuck you, you’re gonna die!’ this and that. They try to intimidate you. It’s like being around a bunch of wild animals ready to eat you. It’s a really tough experience. Words aren’t enough to describe it. You have to live it to understand it.” Steve lived it, adapted, and found his way of surviving on the inside. Leaving music aside at first, Steve started a new audio project. “Every night I met people who would share their stories and I would take voice notes. These stories… not beautiful, but strange, I would record them on my phone. Just to learn.” Steve made the rounds, taking in each inmate’s story, learning all he could about the harsh milieu. One day Steve was speaking with his brother, known as D.O.X.. He told Steve there was an Italian girl coming to some freestyle sessions over in the Death Sentence Quarter, and that apparently she was building a music studio inside the prison.

Riots or church

“In the beginning it was really difficult,” explains Stone Larabik, founder of the prison rap collective La meute des penseurs and original Jail Time Records artist. “Getting a whole bunch of guys together in a prison isn’t a given. Everyone’s got their own things to do. Everyone has to find something to eat. You have to try to captivate them,” Stone says from the studio inside New Bell. Words not to be taken lightly. Before prison Stone was in a special faction of the Cameroonian military known as the presidential guard. Stationed in Gara Boulai on the Cameroonian, Central African frontier, Stone and his battalion were tasked with holding the border. After what Stone describes as a misunderstanding with a stolen firearm while on leave, he ended up getting a hefty prison sentence and was sent to New Bell in 2016.

Well into the 21st Century New Bell is still known as Cameroon’s harshest prison. Overpopulation, lack of oversight, and internal corruption have made conditions in New Bell at times intolerable. In 2005 a riot broke out when one inmate was beaten to death by a group known as the “anti-gang”, a collection of prisoners used to maintain order by the underemployed guard staff. After the attack, the other inmates retaliated, resulting in 15 injuries and a public scandal. “The New Bell prison was originally supposed to house 800 inmates but some 3,100 people (were) locked up there, with about a third waiting trial,” said the prison’s registrar, Jean-Pierre Ayissi Biyegue in 2005. The prison also has a history of attempted prison breaks. In 2017, three inmates made their escape with a fake wooden gun wrapped in black tape. The attempt was deadly for one, the others successfully made their escape. It’s estimated that at the time the prison was overpopulated by 380% (Actu Cameroon).

Within the prison there are neighborhoods that are divided up much like the different sectors of Douala. Stone was sent to the Death Sentence Quarter, and while capital punishment is still a legal penalty in Cameroon, no executions have been carried out since 1997. So, this section of the prison has been for lifers, long sentences, and the “condemned”. Then there’s the Latin Quarter, a dangerous zone where the young’ins from the ghetto make the rules. There’s the Hangar where kids can rest, the Muslim Zone with its mosque, shoemakers, and men drinking chai tea, Akwa, named after Douala’s commercial district, 3ème Age for the older inmates, and Texas… “That’s the Far West,” says D.O.X., who stumbled upon Stone Larabik and his crew during one of their organized rap sessions. “That’s where the big bandits are. That’s a kind of neighborhood you wouldn’t find in Douala. But everywhere else, it’s like a little Cameroon.”

In this little Cameroon guards let inmates set up shops, do commerce, and imitate life on the outside. But two things aren’t allowed, and subject to seizure when the guards come to search; drugs and telephones. Stone, who has been rapping since his army days, ignored the rules, securing a phone so he and his crew could make beats for their raps. “I downloaded, n-Track an application onto my Samsung Galaxy. When I woke up in the morning the first thing I would do is exercise. After that, eat. Then, I’d lie on my mattress with my little phone, hiding in the shade. I’d record my voice on my personal headphones then have my mates listen to it. We talk about it, and do it again. That’s how I spent my time. Hidden in the shade, with a telephone as contraband…”

This is how music was recorded in New Bell pre-2018. But despite the cheap hardware and clandestine nature, Stone kept at it. And took it a step further. “There was no way to express ourselves except through riots or church. So I thought, why not organize a rap collective where the guys could speak freely?” One day, during a dance event organized within the prison by an NGO, Stone and his collective took the mic. Dione, the Italian volunteer behind the event, took notice.

Even in hell you can be free

Dione Roach is an artist and photographer from Italy. Graduating from UEL in London with a degree in Fine Arts, Dione has led a multidisciplinary life, working in photography, video production, painting, and community art projects around the world, including in South America. “I think that being aware of the privilege I had in being exposed to art from a very young age, and being always and unconditionally supported to do so,made me want to share this experience with people that have not received that support either from their families or from their surroundings, or have never been given the tools and means to go forwards with their creative passions,” Dione told Metal Magazine in 2022.

“I wasn’t meant to work there, but after the visit I kept thinking about the opportunities to use art inside.”

In 2018 Dione went to Cameroon to continue her work, this time doing a year of civil service for the Italian NGO, COE (Centro Orientamento Educativo), organizing cultural activities and teaching photography at an art school in Douala. After a visit to New Bell for a sewing workshop, Dione couldn’t get the place out of her mind. “I wasn’t meant to work there,” Dione laughs, “but after the visit I kept thinking about it and the opportunities to use art inside.” She started doing painting workshops. A longtime fan of dance, Dione also decided to set up an event for the prisoners, relying on the network of dancers in her orbit.

It was during one of these dance events that a group of prisoners came over, drawn in by the rarity of an amplified mic. Someone took it and began to freestyle. Dione didn’t know it at the time but this was a member of the prison collective “la meute des penseurs” or “the thinker’s pack”. Astonished, Dione followed up. “I went to one of their rehearsals in the death sentence quarter and it was amazing. It’s just such an extreme situation to be doing that,” Dione explains. “Going to the prison and kind of seeing the guys singing and thinking, wow, even within such a terrible living situation, and maybe even no matter what they have done, you can still have that power to express yourself and seek some kind of redemption or liberation through art.” Dione continues, “You know? Even if you’re living in hell you can be free.”

In the middle of tragedy, in a quarter where everything, literally everything, can be taken away, this group expressed their voice. “Let’s make an album,” Dione told the crew. “I’ll find a way to bring some recording material to the prison.” Dione’s work with the prison administration was surprisingly smooth. There were no objections, and Dione was allowed to build a studio on the inside, with partial financing by the NGO, and some clever partnerships with Italian fashion brands. But there was a hitch. “When we got the studio ready we didn’t have anyone to run it,” Dione says. But someone mentioned a former music producer inside the prison who was going around collecting vocal testimony. Each one looking for the other, the two eventually met. “We immediately had a connection,” Dione explains, “we had the same kind of ideas and sensitivity for the project.” Steve became the studio manager. Shortly after Dione had to return home to Italy for a few months. “I came back and they had recorded loads of music! Not just rap, but all kinds of music with all kinds of different people,” Dione exclaims. “That’s when we had the idea to create a record label.”

Open & closed

In the beginning, Steve was left with the mission to record an album with Stone and his collective La muete des penseurs. But that mission quickly evolved. “I was interested in discovering new talent,” says Steve, “from my time in prison, recording people, I already knew a lot of other artists. So I decided to open the project up.” Between studio sessions Steve would make the rounds throughout the prison, scouting talent, asking those around if they knew any artists, and seeking out the people he already knew had something to offer. Little by little talent began flooding in, some with a background in music, others trying their hand for the first time. “I even had the idea to bring people in just to have a good time,” says Steve. “There’s not just those who make music, but those who bring the energy, the fun… People who are a part of the movement.” People like Ba’a who had never made music emerged as a hidden star. Or Djafar, who had been making music all his life, but didn’t have the look one expected of an artist, and wouldn’t otherwise have gotten a chance. Unlikely characters coming in and out, ready with ideas, or simply there to witness.

In the two years that followed, Jail Time released an astonishing double-sided compilation, Jail Time, Vol. 1, featuring 24 tracks and including 13 artists. The are beats made by Steve, reworked and thought over, selected from an even larger catalog of tracks that have been made and saved over countless hours inside the New Bell studio. As Jail Time grew, and the project became well known within the prison, artists began to compete for opportunities like music videos or the best beats. A new work ethic emerged where each artist was trying to make the best possible song. “Before a concert or before an event in prison, people wanted to get in the studio and make a new song. It created an ambiance where everyone was super motivated and productive,” says Steve. “The studio has a long term impact. Even if there are some disputes and some jealousy, it creates a sense of pride.”

Steve also played a role in broadening the musical horizons of the studio participants. While many had the culture of Western hip-hop, Steve insisted inmates bringing something of their own to the musical foray, whether that be their language or traditional sound. Cameroon itself is said to have at least 250 languages and ethnic groups. This diversity is a source of vast cultural wealth, musically and otherwise. In the Off the Map documentary with Steve, we see him insist to Djafar to bring an element of Nguon culture, a part of the historic Kingdom of Bamum from northwest Cameroon. “I told the guys during a brainstorm session, that we as Africans also have something to share. And if you want people to listen to you, you have to teach people something about yourself and where you come from… Too often we have the tendency to lose ourselves in the culture of others.” The examples, like the backstories and cultural legacies of the inmates, are vast.

There’s Bamum singing by Djafar

the Atalaku drill of Kengol DJ,

singing in Duala by Moussinghi,

and the mbole drill that Steve has been working into Jail Time productions.

It makes for a vast palette of sounds that can be found on the compilation, and a project uncannily representative of Cameroon’s cultural diversity. “We’ll do electro with nguon on top,” says Steve, “hip-hop with Bafia, Bassa, or Duala… It’s a way for us to share, to connect, to see who we are.”

Music is a weapon

“Sitting behind the computer, recording them, listening to the story, I’ve been drawn into their lives,” says Steve. “They are sharing a lot with me through those tracks.” Take Stone Larabik’s track “Père irresponsable” (Irresponsible father). In it, the hardened army man laments the suffering of a life without a father, while making amends with the fact that he, also a father, has been taken away from his own daughter. “It gives you strength, it gives you faith. It’s like a dream,” Stone says of the creative process.

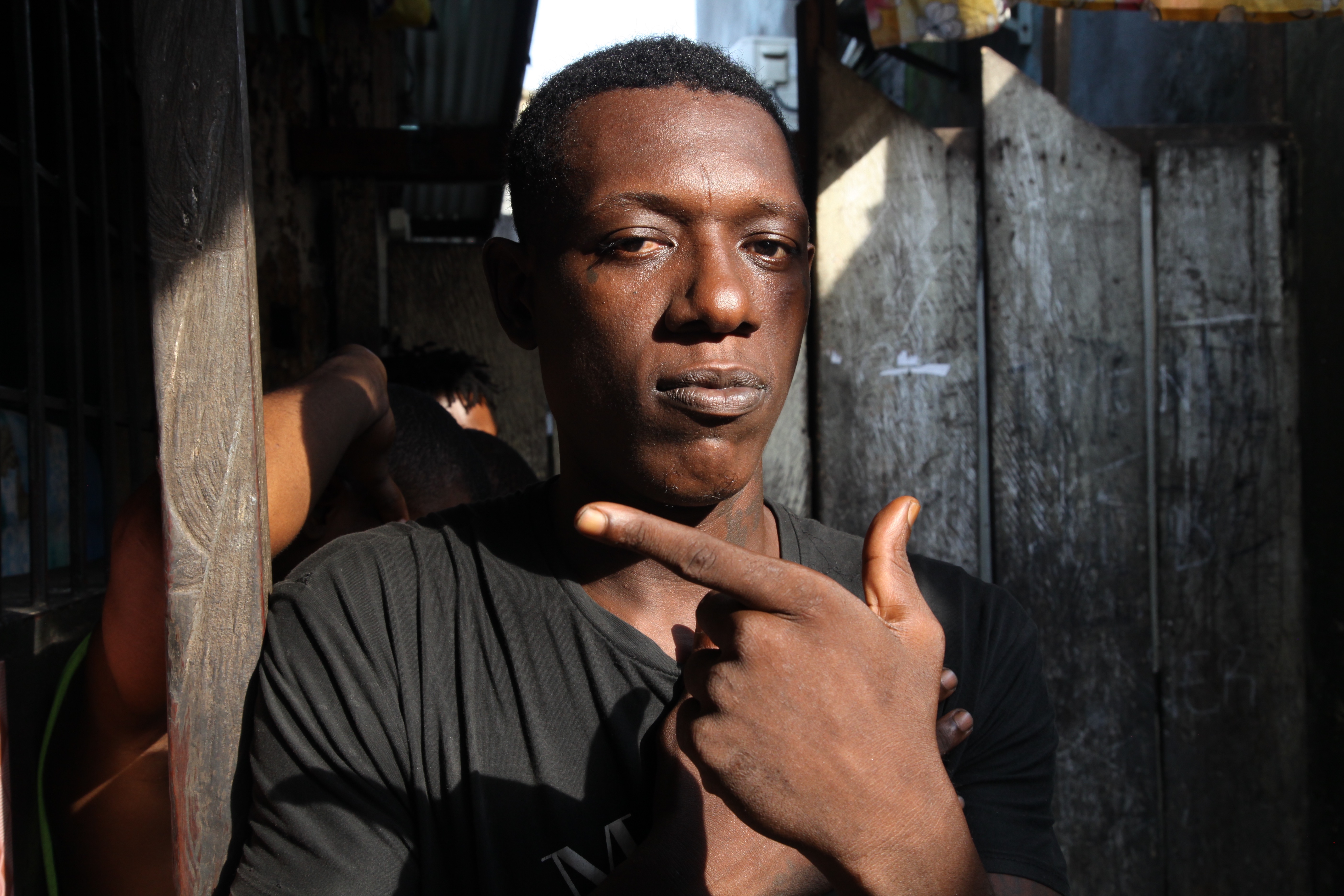

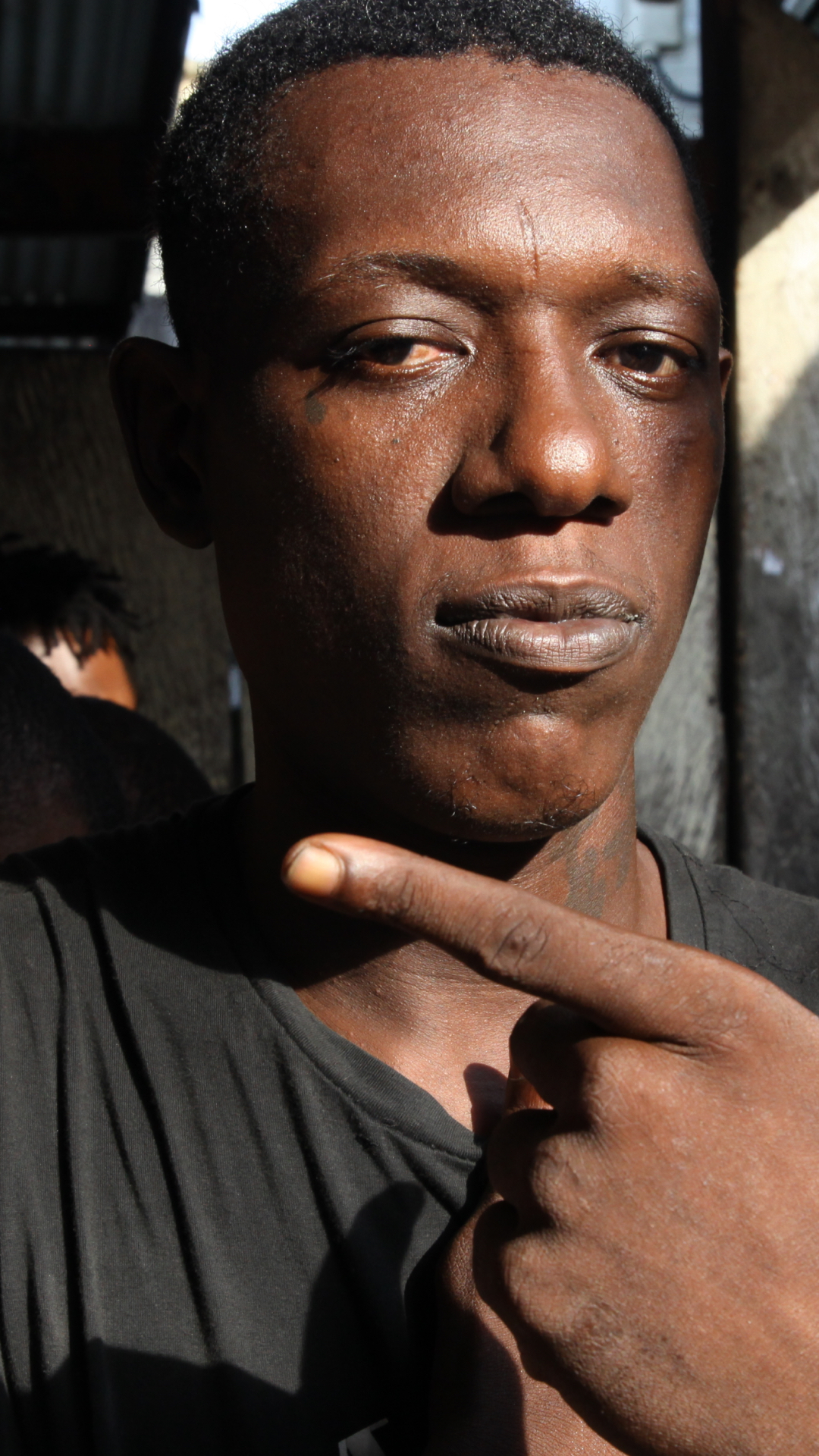

“Empereur is a child of the chiefdom, of traditional practices, of the Duala,” Steve explains, “but he was sent away from his family to live in Yaoundé, and he rebelled into the street.” Another hardened case, Empereur is serving a long prison sentence, unlikely to be released anytime soon. “He is kind of the boss of the Latin Quarter,” Steve explains. But that didn’t give him any priority access to the studio. As the team worked, Empereur would come in, test ideas, using his Sawa mother tongue of the Duala, and little by little earned his stripes. In the studio, he’s on the same playing field as the others, the hierarchies of street life reconfigured into 4/4 measures and clever licks. “He’s hard on the outside, but he knows how to be kind,” says D.O.X.. In the process Empereur can focus on another discipline, recalculate “might is right” relationships, and step into a creative world where sensitivity and collaboration are the way forward.

Empereur poses in the Latin Quarter of New Bell Prison, an area known for its gang activity.

Jeje, born in Nigeria, is one of Jail Time’s only female artists.

When Jeje was a teenager, she was sent to live with her uncle in Douala. While there, she was abused by her uncle who she described as constantly angry, violent, and unreasonable. Eventually Jeje decided to run away and get back to Nigeria and her family. For her escape, she stole what cash her uncle had in the house, and used some of it to pay a man that was supposed to sneak her back across the Nigerian border. During the trip, the man stole the rest of Jeje’s money and abandoned her. Jeje survived on what little cash she had hidden away, before getting caught by Cameroonian authorities, charged with theft, and sent to the women’s quarter of New Bell prison. It’s a small population of roughly 50 female inmates compared to the 6000 in the men’s prison, but the conditions aren’t much better. “At least with music, when I’m feeling a little bit worried, I could go to the studio, try a vibe with the new family, and help me to forget my sorrow,” Jeje says.

Anxiety, fear, and stress are dealt generously from the inside, for women and men alike. “For me it was terrifying,” Jeje says of life behind bars, “there are fights, there’s noise, it’s not easy to be on your own.” Jeje has since been released, with two singles to her name; “Show Me the Way” written and recorded from inside prison, and “This Life” made on the outside. “Making music helped me cope,” says Jeje. “When I’m working with Steve, he gives you confidence, he pushes you to do something more.” For Jeje, Jail Time is more than just music, “it’s the sound of a new chance in life. It’s the sound of freedom.”

Jail Time Productions

Dione and her students are also providing the visual element to go alongside the music. Music videos show the chaotic interior of New Bell with the makeshift cells, stone walls, and crowded alleys. Little corridors and hanging laundry, it can feel like the shots are coming from a marketplace or shantytown. Not to mention the creative energy that explodes from scenes in “SA NGANDO” by Empereur who raps into the camera surrounded by hands of inmates painted red, dancers shaking in blue, comedic violence, loose legged jerking, all in the hectic decor of the prison. It’s astonishing. Dione, who shot the video from the inside, has unprecedented access. “Dione is really loved in prison. Loved for real,” says Steve.

“It gives them a focus,” says Dione of the work on Jail Time Records and Productions. “There’s so much idleness in prison.” Dione has been filling the idle gaps with courses on photography and videography. One step at a time the students and inmates are able to take control, grab the camera, and produce something for themselves. Even Steve has benefited from this crash course. “She’s holding the camera, I’m holding the bags,” Steve laughs about their music video sessions. Steve, now a budding videographer says with a smile, “she gave me her blueprint.”

It’s an internal economy that shows promise. The more music that’s produced, the greater the demand for videos, professionals to mix and master, promoters to push the sound, studio managers… it goes on. It’s a positive counterbalance to the informal and illicit economies that dominate Cameroon’s private sector which includes about 90% of the labor force and 50% of the GDP. As Jail Time Productions develops, with the help of international actors and the charitable donations necessary to get it off the ground, the structure provides an alternative to the illicit trade practices like smuggling, counterfeiting, and fraud that are accessible to ex-convicts but can lead one back behind bars.

And there’s reputable names turning heads. “It feels big and important with the international team involved,” Dione says of their work. The photography and music videos have gotten international press from Vice, NTS, BBC, and Crack Magazine. Dione’s artistic vision, from the stark black and white photography to the physical music videos, are works of art in themselves. The context gives it meaning. “A lot of them were not that serious at music before or always did it out of love or hobby, but never really invested themselves. But now, they take it really seriously. And you see a huge change in the quality of the work from when they started,” Dione explains. “It’s such a powerful message to the world.”

The work starts outside

“At the end of the day it’s cool, all those videos and everything, but the center of the project is the human being,” Steve emphasizes. “It’s about reinsertion. We’re trying to get them a life.” It didn’t take long for Steve and Dione to realize that Jail Time had an even greater role to play on the outside. “When they’re in prison, they’re in prison,” says Steve, “all we can do is make them forget about the pain. But when you’re out, you’re working on the development of a human.”

Recidivism is a global phenomenon that judicial systems around the world seem inept to confront. Cameroon is no different. The reasons are many. Some may end up in prison for non-violent crimes of circumstance, like Djafar who Steve described as being at the “wrong place at the wrong time” without any official ID. But once inside it’s easy to get caught up into the criminal underworld that maintains a vigilante order and offers pathways to petty cash and clout. A field survey from 2020 found that 47% of prisoners in Cameroon are serving at least their second sentence (African British Journal). There’s also the stigma that follows former inmates once they reach the outside. Family members can reject those they see as criminals, employers are hesitant to offer opportunities, and old habits of drug use can crumble any wherewithal that may be left.

And there’s the hundred and one fastidious little tasks that need to get done regardless. “We find them a house when they’re outside. We find them a phone. They lose them all the time. And mostly we want to find them a job. And an ID card, which is the most difficult thing because they’ve often lost their birth certificate,” says Steve, ever-patient.

Moussinghi has been in and out of prison his entire life. During his last stint, which came after a violent interaction with the police, Moussinghi found Jail Time. Since his release he’s been a hopeful case for reinsertion.

Which doesn’t mean things are easy, or the path to the good life is smooth. But so far Moussinghi has been able to remain on the outside, stay focused, and imagine that another alternative is possible. This spirit is incarnated on Moussinghi’s track “Sacrifice” where he explains, “it’s about where you get energy, where you start something, and believe in where you want to be tomorrow,” he continues, “I see changes coming. I’ve got hope.”

Steve has given an emphasis on the development of skills through Jail Time. Computer literacy, production basics, recording, graphic design, administrative management, Jail Time has been trying to give the tools to inmates that allow them to run the project on their own. “A big part of my mission is to create autonomy,” says Steve, “that, without me, the studio still runs.” It’s these kinds of skills, and the discipline required to master them, that can transform into real world opportunities. Each Jail Time member can play a role within the production entity of the collective, because making music is not just about who’s behind the mic. “I started as a prisoner, I became a studio manager, now Djafar is the studio manager…” Steve explains. “That aspect, education, I hold close to the heart.”

A life beyond bars

Histories are written. Sometimes they’re carved onto stone walls, counting down days, names or initials. A scratch. Sometimes they’re scars. Or tattoos with shoddy ink and dull needles. Sometimes they’re written in sound. The testimony of spoken word. But even in the writing of history the truth is floating somewhere in-between. On another plane. Hidden in collective memory, or the dull patterns that take shape on tactile walls in the night. What can we know of a person from the markings on their chest? From a court stenographer’s busy fingers? From the list of papers with CRIMINAL RECORD written in bold on top? And of a prison… where countless lives have passed. Where death and redemption live in close quarters. Who are we to know? Who are we to judge? Jail Time gives the space for those whose history is wrenched around their heart, tensed in the muscle beneath their skin. It’s an opportunity to rewrite what was, to reform the hidden associations that we connect to the ideas of criminal and prison. It’s a chance to realize how we are defined by what we see, and in turn, where we go from here. On empty audio workstations and quiet music studios, Jail Time is rewriting histories. In bureaucratic office buildings and noisy city streets, the collective is also allowing for new stories to exist. One outside of prison walls. Stories where we can be free.